The question of when and why to socialize a young puppy is one where you could easily find many dozens of answers. Unfortunately, many of them start with just a little science, then exaggerate it beyond all bounds. We’ll begin by discussing some of the dog’s early development periods, then see what a few places advise.

References

- Early puppy socialization classes: Weighing the risks vs. benefits from dvm360

- How to Socialize Your Puppy from Karen Pryor Clicker Training

- Socializing a New Puppy from Fetch WebMD

- Puppy Socialization: Stop Fear Before it Starts from CattleDog Publishing (Dr. Sophia Yin)

- Puppy Socialization: Why, When, and How to Do It Right from the American Kennel Club

- Puppy socialization: When and how to socialize your puppy from Wisdom Panel

- AVSAB Position Statement On Puppy Socialization from the American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior ABSAB

- Puppy Socialization from the Animal Health Center

- The Puppy Socialization Project

Followed by an actual textbook, which focuses instead on the science.

Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, Steven R. Lindsay 2000

Stages of Early puppy development

While most of those sites only speak of socialization and some kind of fearful periods, they are omitting dozens of pages which would be needed to describe all the stages and tendencies. For any of those interested, I’ve summarized some of the often missing detail here to fill in the gaps, but most people will be fine just skimming through this section.

In these below periods, the dates, durations, and overlap will vary between breeds, and even individuals. Typically, the smaller breeds will advance much faster through the later stages.

- Neonatal period, birth to 12 days.

- Transitional period, 12 to 21 days (1-1/2 to 3 weeks)

- Primary Socialization (3 to 5 weeks)

- Social fearfulness 5 weeks, peaking at 12 weeks

- Secondary Socialization (6 to 12 weeks)

- Social Dominance 10 to 16 weeks

And while many articles emphasize how important this early development can be, some leave you with the all-or-nothing thought, and none of them really speak about what happens later on. Many of the dogs I’ve worked with have ranged from 5 months to 5 years old. Many of those 6-months to a year were backyard dogs who had been adopted as cute pups, but spent most of their lives living in the backyard with little attention, until being dumped as they grew up with no training. Some had already spent several months in an animal shelter. All of these dogs were long past early puppy development periods. Many of them came here due to behavior issues.

For all of that, the majority of them learned basic socialization with both people and dogs, and were house, potty, car, store, and leash trained in only three to four weeks.

Neonatal period, birth to 12 days

Regarding (brief) early handling and other infantile stimulation experienced prior to weaning, those dogs left undisturbed during this period were found to be consistently more emotionally reactive (general and fearfulness) as adults. The handled animals instead adjusted more quickly to later changes in their environment.

Transitional period, 12 to 21 days (1-1/2 to 3 weeks)

Eyes open and beginning directed movement on limbs. Seeking contact comfort in addition to nipple feeding.

Socialization period, 21 to 84 days (3 weeks to 12 weeks)

Primary Socialization (3 to 5 weeks)

Kinship recognition and acute separation distress. Preference for bedding with an odor of littermates over that of non-littermates. Group coordinated activity and social play begin, with both aggressive and sexual encounters occurring, including stalking, pouncing, and shaking. If with littermates, mouthing begins development of bite inhibitions.

Insufficient socialization during this period tends to result in a variety of later issues, such as bond guarding or initially being overly fearful of other dogs or people.

One of the outstanding changes in behavior at the beginning of the period of socialization is the tendency of puppies to respond to the sight or sound of persons or other animals at a instance. The 3-week-old puppy approaches slowly and cautiously toward a human observer seated quietly in its pen. It finally comes close and starts nosing his shoes and clothes. After this, it may start to wag its tail rapidly back and forth. The tail wagging itself appears to have no directly adaptive function, but is simply an expression of pleasurable emotion toward a social object. What effect it has on other dogs is difficult to tell, but it seems to have the same effect on human observers as the smile of a child; i.e., it is a reward for the person who has initiated a social contact.

Scott and Fuller, 1965:104

After week 5, puppies become progressively more cautious and hesitant about making new social contacts a growing fearful tendency that appears to peak with the close of the socialization period at 12 weeks. Prior to this time, puppies are virtually immune to lasting negative impressions, readily recovering from fearful social experiences without apparent effect or permanent avoidance learning. After week 5, the recovery time following aversive or fear-eliciting stimulation is significantly protracted. This pattern of development culminates in the emergence of adultlike brain activity and the appearance of a particularly sensitive period for fear imprints around 8 to 10 weeks of age.

Fox, 1966c

Secondary Socialization (6 to 12 weeks)

The process of bonding and social conditioning within the context of the human domestic environment is referred to as secondary socialization. For most purposes, secondary socialization begins in earnest when a puppy leaves the mother and litter- mates to begin life with a human family.

Stephen Lindsay

Juvenile period, 84 days (12 weeks) to sexual maturity

There are several named development stages around this time, which often vary somewhat as to their beginning and duration, and they may also overlap. As for scary stuff remembered for life, that’s mostly hokum (except for imprinting, see later). An exploring pup that age will typically be eager enough to get into trouble, then will squeal and run like hell for a minute. You’ll often see this dozens a times each day, yet none of these will be remembered for life. With most forgotten in just minutes.

While many articles commonly mention a “sponge brain” reference for young pups rapidly soaking up information, that’s only partly correct. That is because a good part of what we see and remember is determined by our brain’s interpretation of what happened. If both an adult human and child observe something new and startling, most often the adult will have absorbed far more detail than the child. This is due to both increased cognitive maturity and having a larger store of previous knowledge to draw upon for interpretation. Conversely, with a less detailed and more repetitive scenario, young children will generally learn a new language faster than many adults.

With young pups, the same thing is seen in training schedules, where certain types of training will not be effective until the pup reaches an appropriate age. So early learning in pups may be faster for simple details, but may not ever happen for for more complex ones.

How Critical is Early Learning?

Moving on now to reviewing selected portions of the reference articles on puppy socialization. So many of opinions are found repeated in so many places that it’s well worth bringing a few forward for some discussion.

During your puppy’s first three months of life, he will experience a socialization period that will permanently shape his future personality and how he will react to his environment as an adult dog.

American Kennel Club, AKC

Yet the puppy socialization does not end at 16 weeks of age, and surely not the only 12 weeks they indicate. That is only an accelerated period of learning during early puppyhood, which is simultaneously restricted by limited cognitive development. For instance, while it is important for young puppies to learn puppy play, a few months later they will then need to learn the different teenage play. Something they can not really learn during the early learning periods. Similarly, at a later age they need to select and develop the adult play skills they prefer. And these preferences often will not be established until after they have already tried other variations. If you check the training schedules for many types of service dogs, you will easily see how the training complexity does not increase until they are old enough to more readily absorb the material.

How come all the experts talk about the early accelerated learning, but none of them ever seem to mention the limitations during that period due to waiting for later cognitive development and physical maturation?

As for the AKC’s claim of permanent shaping of personality, there are thousands of shelters and rescues adopting out hundreds of thousands of young dogs who had little or no socialization during their first few months. However, none of that was permanent, and most of them end up learning quite well. Alternately, kennel-dog syndrome (isolated confinement) has been shown to counter some early socialization, either temporarily, or for far longer, further proving that early learning is often not permanent.

My Jack Russell Terrier, Jonesy, randomly barked at people wearing boots for a year, and he barked at one of my assistants because he didn’t recognize her when she was wearing this hooded sweater.

American Kennel Club (AKC)

According to the AKC, the dog needs to become familiar with those and other objects, such as brooms, unfamiliar people (especially men) (and probably everything possible under the sun?). Or, might there be a better and easier way to do this?

It is their sensitive period for socialization and it is the most important socialization period in a dog’s life. Puppies who do not get adequate socialization during this period tend to be fearful of unfamiliar people, or dogs, or sounds, objects and environments. While some owners focus just on exposing puppies to many people and situations, it’s important to actually make sure that the puppy is having a positive experience and learning something good. While some owners focus just on exposing puppies to many people and situations, it’s important to actually make sure that the puppy is having a positive experience and learning something good.

AKC

As I related above, hundreds of thousands of shelter dogs have overcome their missing this allegedly most important period. And yet I’ve never had any issue with Ugg boots or hooded sweaters, because I instead taught the dog how to respond to new and unknown stuff in a way which allows him to both feel more secure, and to learn about them.

Sadly, about their only suggestion on making something a positive experience is in feeding the dog some treats. How about instead having a learning component?

These puppies have never seen a child, but because they’ve been socialized to so many other things by 7 weeks of age, they immediately accept this child as safe. The child also knows how feed them treats and this helps them associate her with good experiences. Because these puppies have already been handled a lot, they let the child pick them up and relax regardless of the position she holds them in.

AKC

Frankly, that’s a truly horrible approach. First, that child must either be well supervised or already familiar with handling pups. Later on, if that pup should meet some unruly kids and expects only the same gentle treatment, you’re heading to either a very scared dog or a bite incident, perhaps both. Instead of stuffing their mouths with treats, you could try teaching appropriate behaviors.

If the dog learns how to react to the child in an acceptable manner which also gives the dog some choice and they enjoy the results, then that would be a positive experience resulting from their learning.

Imprinting

Imprinting is a learning phenomenon distinguished by three primary characteristics: (1) it requires a small amount of early exposure, (2) it occurs during a relatively short sensitive period, and (3) it exhibits long-lasting and durable effects.

The imprinting period is usually bounded by relevant developmental processes. The learning or lack of learning experienced during this impressionable period is largely irreversible.

In its broadest sense, imprinting is a process (limited by the aforementioned parameters) whereby an innately prepared species-speciï¬c tendency or pattern of behavior is brought under the control of a preferred stimulus, releasing agent, object, or situation.

Stephen Lindsay

These are the behaviors learned during early development which often tend to persist through much or all of the animal’s life.

But only particular behaviors are sensitive to imprinting, and often only during specific developmental periods. One such case found in research is in teaching the dog retrieval skills around week 9 as opposed to much later on. Potty training is most efficient around 7-9 weeks of age and more likely to be persistent. Early socialization with other animal species also seems to be persistent. While there are likely more items, this does not apply to the majority of experiences and items you teach a young puppy.

Even regarding socialization, a young pup might imprint on basic social behaviors with young children. But it’s not until later on that he can learn how to avoid or control unruly kids, so the early imprinting does not define all the behaviors later involved with any of these actions.

The Missing First Step

Many of the articles focus on gently exposing your puppy to people, places, and things. Then perhaps adding items ranging from walking on different surfaces to various sounds. Well, I’ve had many somewhat older dogs who lacked socialization and were scared of many things, but I’ve never started with their suggestions. Instead, my very first focus is on security and some amount of control. To gently guide the dog’s behavior, watching how he responds to ordinary things, experimenting to see what response from you seems to make him feel most secure, and noting what behavior he does then. I then put that behavior on cue, for later use.

Bono was a scared young Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog, who felt most secure next to Bandi. He’d go out to explore, then run back to Bandi when scared for the first few weeks.

Next comes a portion of Karen Overall‘s Protocols for Deference and Relaxation, adjusted for the pups age. The focus here is on teaching the pup some very basic behaviors which will allow you to better communicate and guide his behaviors.

Then, we start exploring the world, starting with simple and quiet stuff. If the pup gets too excited or nervous with something at this point, we just skip that item for later on. Each time, I use the prior learned behaviors to influence his responses, and cue his established security protocol if he ever seems scared and unsure of what to do.

On the topic of fear, why is it that nearly all articles say to avoid this at all costs? Sooner or later, your dog will come up against something which is scary, and there will be fear. If he never learns how to handle that, some dogs may panic. But, this is the time to start teaching him how to cope with those situations.

Earlier, I mentioned my preparing unsocialized dogs for adoption in only four weeks. I’ve seen other people take in similar dogs and spend months on that effort, because they skipped these first steps and focused instead on treats and only positive experiences. Obviously, a very young pup can only learn a portion of this every few weeks as their cognitive development advances. But most should be complete with basic socialization in under five months of age.

As is often the case, the devil is in the details. The details of how this is done are all important, but very difficult to communicate in any article. Even with demonstrations, you’d need nearly a dozen dogs with different personalities, fears, and other characteristics in order to demonstrate how those variables could be well handled. But, in nearly all cases, the same stages are followed.

And, the next time you see a dog either jumping all over you or running to hide, and the owner says it’s because he’s still a very young 6-month old (or even a year old!) puppy, feel free to roll your eyes as you walk away.

How is this Learning Done?

Dogs learn in two ways; they learn by association (classical conditioning) and they learn by consequence (operant conditioning).

Clickertraining.com

Actually, that’s a no. One of the most popular types of operant conditioning is called positive reinforcement. The most common failure there is the lack of a dog forming an association between his behavior and the following reinforcement. This is a typical case of people trying to simplify something to where it no longer has any distinct meaning, and they never seem to notice that.

Learning in young pups is actually the same as for older dogs, with the following differences.

- The pup has less prior learned behaviors to either build upon or attempt to change.

- As he’s not yet physically mature, some activities are more difficult, and he will tire more easily.

- The young pup is not cognitively mature, so memory and attention span are reduced. While he may be very receptive to early learning lessons, many of the details may yet be beyond him.

Do First Impressions Matter?

Puppies are always learning. What puppies learn in the early days has an enormous influence on the dogs that they become, because it is what they learn first. Puppies certainly don’t start off as blank slates, genetics play an important role. Nevertheless, their first experiences with new stimuli shape how dogs respond to those stimuli later on in life.

Karen Pryor Clicker Training

While it may at first sound right, is it really true? Do you still react to what scared you at two years old? Notice their use of (sic) science: because it is what they learn first.

Most fearful dogs I work with are afraid of nearly anything new, and it typically takes three or more repetitions before they calm down enough to start learning about it. And it’s only then that they begin to notice more related detail, can better examine how their response makes them feel, and may alter their own response to improve that.

And very young pups will always have some scary experiences, but almost none of them are remembered later on in life. Just think about that one. If you first assembled something one way, then assembled it differently for hundreds of times for months, how much will that first time impact your later behavior?

Unless it’s a very traumatic incident, first impressions have very little impact on puppies, and except for imprinting (see above) there’s just no reason to think otherwise.

The aim is to have enough positive experiences that new experiences can be taken in stride at any stage of life.

Karen Pryor Clicker Training

Let’s see now, if I start out with many positive experiences then I will somehow magically know how to handle new and very different experiences which happen later on? So if the dog learns how to walk on a leash, he’ll later handle a busy store or a car skidding?

Instead, what if the dog learned how to handle many classes of situations, with behaviors that you find safe and acceptable, and which he also finds satisfying? And that includes situations which he wants to avoid. An emergency recall, for instance, would handle some issues, together with a few stores and traffic training. But in all cases, it’s the learning and not the positive experiences that provides a solution.

A young pup meeting new social adults and learning manners.

Puppy Body Language

This section refers to The Puppy Socialization Project, from Marge Rogers, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, CCUI, Certified Fear Free Professional, and Eileen Anderson, MM, MS. Here, Marge gives her take on body language, which may somewhat explain her claim of being something called Fear Free, which I’ve spoken about elsewhere.

Marge then claims that, by going down her checklist, you can decipher your dog’s body language. However, she never seems to realize that the exact same body language can mean any of several different things. That a dog licking his nose may just have an itch. That there are many cases during play where the dogs will deliberately assume some body language to match the game. That interpreting static body language without considerable history has a very high error rate, as opposed to dynamic body language, which includes the dog’s subsequent behavior in response to a stimulus.

Which brings back memories of running shelter playgroups, where I’d occasionally hear some (alleged) expert dog trainer explaining to another person what a dog’s body language really means. However, they were always outside the fence, and it was the two of us inside and running the playgroups who had to accurately predict what each dog is about to do. And that accurate prediction is the only true test on understanding a dog’s body language.

Intensity in Puppy Socialization

Intensity from Threshold

While Marge gives a great deal of advice here, I typically focus on an articles notes for the thresholds and results, as that’s where you measure the intensity that should be used. And here’s what Marge has to say on that.

Trainers often talk about keeping dogs under threshold. What does that mean exactly? Let’s go back to Merriam-Webster.

Marge, Intensity and Thresholds in Puppy Socialization

The point at which a physiological or psychological effect begins to be produced.

Threshold. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/threshold. Accessed 2 Oct. 2021.

That’s a good definition and in keeping with how dog people often refer to threshold. Since it’s a general term, there are thresholds for lots of different things and experiences. But for dogs that bark and lunge at other dogs or people, what we mean when we talk about keeping the dog under threshold, is to stay below the point where he is physically reacting or overly stressed. This term is also relevant for dogs or puppies who get over-excited or too stimulated by the environment. We want to choose an environment or practice set-up that is low enough intensity to keep the dog from crossing the threshold between being able to learn and being over-stimulated, worried, or reacting to his surroundings.

Marge

Okay, sure, but how on earth does she equate having any physical reaction at all to the dog being overly stressed? If I pull out a high-value treat and the dog begins to fidget a little, is he really overly stressed? And she claims that any dog reacting to his surroundings is less able to learn? That is not true according to well established science!

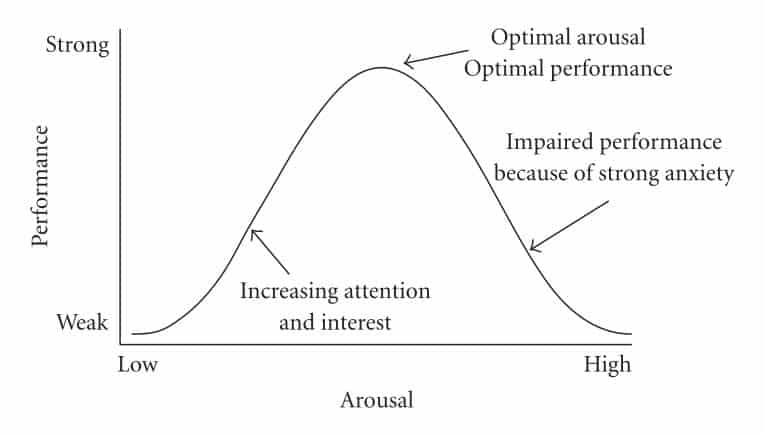

In psychology, one very well-known law is from Yerkes and Dodsen, first noted way back in 1908. One that I’ve previously cited to explain how to control the threshold during desensitization. According to that law, Marge is only using one extreme, and rejecting the area of greatest learning. Instead, my explanation on desensitization showed how to find the best intensity for learning.

How Do You Know If You Chose Wisely? We want you to remember the faces of the puppies below.

Marge

In my opinion, learning is measured by your subsequent response to a disciplined stimulus. And that could range from completing a written test, to fetching a thrown ball. But, apparently, a CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, CCUI professional like Marge only looks at happy faces as the most important items? So, how does one become a certified behavior consultant with no knowledge of very basic psychology, and who only uses ordinary dictionary definitions?

- CPDT-KA Certified Professional Dog Trainer – Knowledge Assessed (she passed a test)

- CBCC-KA Certified Behavior Consultant Canine-Knowledge Assessed

Unlike much obedience training, socialization consists of learned behaviors which the pup will utilize without any prompting or cues from you. Since some of this consists of acceptable behavior in avoiding some undesired or scary situations, looking for a happy face makes no sense at all.

Intensity from Behavior

Instead of Marge’s approach, I use the same criteria as I did in desensitization, as both involve gaining some understanding of a scenario and developing appropriate behaviors for coping with it. This is all part of effective communication and compassionate teaching, taking into account here the young pups limitations in dealing with complexity.

For a fearful dog, their expression and even most body language may not change while learning new things. However, their behavior will tell you the best level to use.

In Conclusion

Young pups will go through several developmental stages, which can be used as a guide for their activities and learning. The methods used are similar to those for older dogs, taking into account some listed differences. The young pups will very rapidly pick up some behaviors but will lack the physical and mental maturity to learn many details until they are older, so you should tailor your expectations for this.