Table of Contents

What to Talk About Here

As is often done, I could take a portion of a single topic or area and just write about that. For instance, I could collect a bunch of pictures and go into the interpretation of dog body language. However, there are many books and courses that already cover that. Instead, I’ll try to speak about where they leave off and what they don’t tell you. Similarly, in a number of other areas, I’ll touch on popular ideas and purported scientific results, and try to give some context and completeness to them.

References

In this discussion, there are several references and quotes from Dog Psychology. While I largely agree with that article, I feel there are several places they have not fully qualified their advice.

I also speak about the Academy for Dog Trainers, founded by Jean Donaldson. In browsing through dozens of available schools, they appear to be the only ones who cover everything I feel is basic in this topic.

And the late Dr. Sophia Yin on Dominance.

Then Steven Linsay’s three-volume collection titled Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training. A classic in the field, this can be a difficult read for those without a background in behavioral psychology. However, this may be the single, most complete, and detailed text available, and it keys into a great deal of research in this area.

Karen Overall’s Clinical Behavioral Medicine for Small Animals. An excellent reference for behavioral issues with dogs and cats. Curiously, the 1st edition included a great deal of explanation, while the 2nd edition is completely reformatted as a list of protocols or recipes for behavioral issues. One possible implication being that most people were more interested in quick solutions than in understanding.

Dog whispering in the 21st century, in Examiner by Prescott Breeden. While the article is somewhat focused on an examination of Cesar Milan, Breeden takes an unusual approach of trying to use and define actual scientific terminology instead of a dumbed-down and casual approach that loses detail and becomes ambiguous. I wish that some of the popular dog books would take his approach.

A Fresh Perspective Dog Training. A trainer claiming proprietary methods. One wonders how he has kept it a secret. (While this article was from 2014, they have apparently closed their business in 2016.)

The Rules and the Behavior

In working with dogs, there is a great deal of scientific research to support modern behavioral based training techniques. However, no two dogs are the same, and there are only a few rules which always apply.

- Primary Rule: The Dog is Always Right

- Second Rule: One Size Does Not Fit All

- Third Rule: Nothing is Black and White

In any interactions with a dog, you are trying to predict their behavior. If your theory says one thing and the dog does another, you are simply wrong and you need to adjust. Too many times I see dog trainers and even behaviorists spending more time and effort trying to prove or justify their theories and opinions, and too little time in watching and understanding the dog’s response. They shouldn’t be telling me how good they are, the dog should be doing that.

Far too many books try to give simple and inflexible rules for situations. Many say that, in canine language, a frontal body approach to a dog with eye contact can be taken as a threat or challenge. Yet, this is something that people naturally do, and have been doing, for the more than the 50,000 (or 12,000, or …) years that dogs have co-evolved with people. So, some dogs will take this as a threat, others will simply ignore it, and some may see an invitation to approach or play. For any particular dog, you need to learn how to prompt and understand their reaction. And even “eye contact” is misleading here, for there is a large difference between casual eye contact and an intense stare. Try that with your friends and watch the difference, using a relaxed approach versus an aggressive one.

And what about Leader of the Pack? There, the same thing applies. Some people tend to be leaders, others look for a leader to follow, and some stand apart as individuals who will only accept an equal companion. Also, even the leaders are sometimes followers. Look around and you’ll find all those types with our co-evolved canine friends. Yes, most are followers, which is also quite true of people. And dog leadership is situationally fluid, which means the leader(s) may vary with the situation.

As for the Pack component, current research indicates that a pack of dogs is just like a gaggle of geese. Simply a group with no special characteristics. And if you’re still stuck on wolf packs here, go check with a real expert on that, Dave Mech.

So, with eye contact and pack leader rules, neither of them is really true.

More Behavior and Instincts

Looking in Dog Psychology I do see some very reasonable statements which agree with other studies and my observations:

“Observations of free-roaming dogs throughout the world reveal that dogs are social animals that are scavengers, not predators, and live much more solitary lives, as it does not benefit a scavenger to share limited resources with a large group of other animals. These dogs may form loosely knit groups, with animals joining and leaving randomly and frequently, a trait not seen in wolf packs.”

“Further, the domesticated forms of wild species will, as a general rule, revert back to their original form after being feral (wild) for a few generations. Dogs, of which there are many feral types throughout the world, have not reverted back to wolves either in appearance or behavior.”

However, these are free-roaming dogs. Those who live in our cities will modify their behavior for the different environment. Similarly, there have been studies on groups of dogs by the dumps of major cities, and their behaviors are also a bit different.

Many dog instincts also follow the same route, and nearly all dogs have an instinctive urge to pull against resistance, such as a leash. I recently worked with several Cattle Dogs where I saw a woman having a very hard time walking one of them. She was a large dog and the woman could barely hold on to her. Going over to help, I walked that dog for a few minutes. Avoiding any constant pulling on the leash, I briefly and gently signaled the dog when needed, then added slack. In just a few minutes, the dog was walking just fine. Testing this, I returned to a constant tight leash, and the dog responded with a constant pull. Yet, three other Cattle Dogs did not do this. Instincts are tendencies that may be expressed to varying degrees, depending on both genetics and later experience.

Curiously enough, on returning that dog the woman found her problem returning. From instinct or whatever, the woman simply wasn’t able to stop pulling the dog.

The Body Language

In the last few years, several books have come out about understanding dog language. While they can be helpful at times, many ignore two important aspects. First, both the meaning and relative intensity of a dog’s body language can vary quite a bit between dogs. Second, there is a difference between static and dynamic body language.

For that, I demonstrated a classic case some time ago, where I had two Rottweilers sitting. I slowly approached each one, holding a ball in my hand. In both cases, the dog’s heads went up, their hind legs tensed and their ears fully flattened against their heads. Looking at the mouth, forelegs, and elsewhere, they appeared nearly identical. Several trainers insisted these were both aggression, that the dog is afraid of me, and may bite if I approach.

With the first dog, I slowly approached her side and extended my hand. She turned her head, showing teeth and a deep growl while raising her rear and only slightly backing up. She now showed every indication of being ready to bite if I approached any closer.

But the second dog looked entirely at my hand, tilting her head, her hind legs starting to quiver and a foreleg raising. I then threw the ball. She took off after it and I sat there petting her after she brought it back.

Here, the static indicator was ears flat against the head, which is really indecisive anxiety. That means the dog is anxious about something but does not know what to do to control the situation and get the results she wants. As soon as I made a prompting action, that was only then resolved into either fear-aggression or ball-chasing. Only by interacting with the dog could the difference be seen. So in applying a conditioned stimulus I invoked a dynamic presentation of body language.

Comparing the two, the books never tell you that static indicators have a predictive accuracy that can be very low, while dynamic ones are quite accurate.

On Aggression and Learning

Another violation of the Third Rule can be found on Dog Psychology. Here, they say in speaking about aggression that:

“When a dog is pushed to the point that it reacts aggressively, the sympathetic nervous system, which controls what most people know as “fight/flight” response, becomes engaged in the brain. When this area of the brain is engaged, the dog’s digestive system shuts down, as does the dog’s capacity for learning.”

But, do all levels of aggression have the same effect? Sometimes a show of aggression becomes a learned behavior, as in the barrier aggression that prompts many dogs to bark and sometimes growls at you as you pass by their cages. In most cases, just by opening the door and stepping inside you are then greeted with a friendly dog who welcomes your visit.

Or one dog may be startled and show a flash of aggression before recovering, while another is scared enough to back away and growl, a third dog reaches a state of panic and attempts to flee at any cost, and a fourth one exhibits a phobic reaction. At each successive and higher level, there is a reduced capacity for learning, reaching practically a zero at the phobic level.

Yes, there is a level of intensity where their statement certainly applies, but the Third Rule applies.

Further on that rule, there’s the famed Dog Whisperer, where most everything is reduced to dominance and submission. Another case of the guy selling hammers who sees everything as a nail.

Walking dogs and leash control

In my experience, this seems to be one of the hardest things to teach. No, not to the dogs, but to the people at the other end of the leash. I’ve given up trying to teach many shelter dogs to walk on a leash, as people then come along and teach them to keep pulling. While I rarely engage in pulling contests with dogs, the Second Rule still applies. There are some dogs that, from their disposition and experience, will simply not stop pulling in that environment. Unless I can get them out of that environment and apply appropriate methods, I simply can’t change that behavior at the shelter.

For dogs pulling strongly, I use the leash as a safety and signal device, not one for constantly restraining. When a dog starts to pull, I give two quick and gentle tugs on the leash, tell them “easy”, then immediately give it slack. The two tugs are easy for the dog to distinguish from her reaching the end of the leash, and there is no constant pull for her to resist. On this, I find that most dogs respond far sooner to the two-tugs than the voice command, but a few go the other way. By always using both until the dog starts responding, then alternating them, the dog eventually learns both. With that, my leash correction is just a mild communication.

And if they don’t briefly stop pulling, then just stand there. No, not forever, but just until the instant the dog stops. Each time you start to walk, treat their pulling the same way. For some, count on having to repeat this several dozen times in even the first walk. This is strictly for hard pulling, with actual leash training coming next.

While there are several other variations, the most effective method I’ve found also takes more attention from the walker. When teaching anything, the first step is always to have the dog stop and pay attention, so I start there. Once the initial excitement has faded, and if you’re in a quiet area, most dogs will respond to a stop command, where you slightly jiggle the leash, calmly say stop, and immediately stop moving. Even dogs who often pull will stop for at least a half-second, and that’s all we need at the start. A stop is much faster, easier, and more useful than something like a sit. As soon as the dog is settled for even a half-second, tell him to go as you start walking. Now comes the work, as you randomly do this 20-50 times each walk. As he gets better at it, extend the time to several seconds, and don’t forget some light praise.

What about using sit instead? First, because the minimum sit would still take several times longer. Next, because you will soon be following this with other commands which can immediately be done from a stop, but not from a sit. And how about using treats to reward the stop? No, because this not only takes much more time than the stop, but that the permanent reward for the stop is the dog being able to continue walking and go over to sniff a bush. Whereas the treats would be a temporary reward which would soon be phased out. And with one of the key items to rapid leash training being high repetition, this should be as quick and effortless as possible.

If you’re later trying for 5 seconds and the dog starts to break in only 2 do not fight it, but use what you have and just keep going. Then slowly introduce more actions, as once the dog has stopped a sit or turn around becomes easier. And if you then start this at a large distance from other dogs or distractions, you can slowly close down that distance. This is also a method that works quite well with multiple dogs, and I’ve both handled and taught several at a time. Even when they’ve become reactive from something surprising us, they still react to the stop for just a few seconds, giving me a chance to change direction or take some other action.

Should you use verbal or leash control? Some dogs will start better with one or the other. But, over time, and especially if you are walking multiple dogs, the verbal commands will be more convenient. While the verbal stop should be distinctive, and you can surely start with the dog’s name, don’t make it a shout or command voice. It will be far more convenient to have your dogs respond to your normal voice, especially if others are around. Remember, apply much patience and many repetitions here.

Walking my dogs, when one wants to stop and sniff I just say wait for ____, and the others stop. When he’s done, I just say go and start walking. If other dogs are about to cross our path, I just say stop. Notice those three words are simple ones which are commonly used, and I’ve just set it up so that stop is more immediate than wait. With many dogs I’ll then add around, which is especially useful with multiple dogs (or young pups) when one has wound the leash around you. That gets followed with a few more useful ones, like sit, left, and right.

An added benefit to verbal commands comes in when you drop the leash to start off-leash training. Some additional commands such as come and stay with me can be started on leash, then extended. As for a formal heel, I’ve never actually needed that, and I tend to avoid commands which don’t allow the dog some degree of freedom.

And the special tools?

But, what about special front-loading harnesses, muzzle halters (e.g. Gentle Leader), and all the other stuff, like prong and choke collars? Simply, they are all physical constraints, teaching the dog to respond to physical coercion. Some harnesses or halters may be useful at the start, and also for those cases where the person does not or can not really leash train the dog for other reasons. Those situations sometimes occur, but remember that the leash itself, no matter what it’s attached to on the dog, is still some amount of physical coercion. As for the harness explanation and guarantee:

Having a front clip means that a non pull harness takes the advantage away from your dog and discourages them from trying to pull on the lead. Whenever they try to pull using their chest muscles, the harness will ensure that they feel uncomfortable enough to learn to stop doing so.

Compared to a regular collar, they are saying that something pulling on chest muscles is less comfortable than something pulling on your neck? And if the dog turns, the leash is now wrapped so that your pull is not in the direction you want them to go. And pulling together with being uncomfortable equals an aversive.

How long a leash to use? Sure, I can teach a dog leash control with only a 4-foot leash. However, I can always do this faster with a 6-foot leash. With a few problem dogs, I’ve even gone to a 12-foot leash while teaching them. It simply makes it easier to apply clear corrections while minimizing pulling. If the dog hits the end I can briefly stop him, while feeding in some slack so that there is no constant pulling. And, once they will walk well with a 12-foot leash, it is easy to start reducing the length to whatever you need.

Princess was a Miniature Sheltie who had spent 8 years at a hoarder, and would always run away from people. She would panic with anything less than a 20-foot leash but quickly learned to tolerate that and the leash training then began.

With time and practice (a few weeks), that slowly came down to a standard leash, and then learning social skills with other dogs, as she had spent years alone in a kennel.

From trying to run away, she ended up being the Leader of the Pack.

There was a curious incident the first time I walked my newly adopted Bandi through a local store. This woman walks over to me and explains that she was just with a dog trainer. That I was walking my dog wrong, as the dog should always be walked on your left side. I explained to her that the dog doesn’t care and that’s only a human rule, and it’s also not the real rule. What it actually says is that you should generally walk your dog on your “weak” side, which frees your dominant hand for use, and most people are right-handed. So much for dog trainers giving rules without reasons.

Walking the Walk

Why do we walk a dog? One reason might be exercise, for both you and the dog. Another might be taking the dog somewhere with you, perhaps to a store or walking through a crowd. The third case is simple enjoyment. When we take a walk for pleasure, we’ll enjoy the weather and look around at different things that we find pleasing or interesting. While they are also visually motivated, we know that dogs have a much keener sense of smell and enjoy checking out various odors they find along the way. For many dogs, this is a large part of their enjoyment of life.

But, so many times I see people prodding and even yanking a dog to keep them walking along. Some people were even taught to walk dogs on 4-foot leashes for better control, but that restricts them even more. I generally use a 6-foot leash and allow them a “reasonable” time for sniffing around and exploring. If he catches an interesting scent and wants to go back several feet to check it out, we do that, and when I say “wait for Martin”, the other dogs stop until he’s ready to go on.

How much difference does this make? Sometimes, a great deal. I recall one dog at a shelter had never been walked, and I learned of this when watching somebody trying to walk the dog, a large guy who would just lay down from fear and refuse to move, having to be dragged or carried. I took over and shifted the emphasis from getting the dog to walk, into gently encouraging the dog to explore and get familiar with the world. Every time he stopped, we stopped. The first walk was very short and slow, but by the end of the week, he would bounce out of his run and could be walked by anybody. I never again saw him lay down in fear.

Another dog showed similar behavior and was walked by one person for perhaps five months. She finally managed to be walked okay, but only by that one person, and was still scared of the world. After a few weeks of my walking her for her needs, she improved enough to take her on home trips and through PetSmart. A few more weeks and she would comfortably walk with a crowd of people. Along this route, she would occasionally get scared and sit or lay down. Each time that happened I would stop and spend a few minutes petting and reassuring her, then she’d be ready to continue. The first time through PetSmart this happened about a half-dozen times in 1/2 hour. The next week, she walked all through without any problem. So while that first person was eventually able to walk the dog, she ignored the dog’s needs and there was only a little learning.

Behavior Modification

In Dog Psychology they briefly discuss general behavior modification and contrast that to suppression methods. While I agree with their comments on desensitization and counter-conditioning, I’ll add another component I feel is often useful and important. Similar to their article, this one will have some more technical terminology.

I deal with many scared dogs. There I will often see conflict in the dog, where their interest drives them forward until the fear is high enough to drive them back (approach-avoidance conflict). In these cases, people often do not realize that generalized instrumental training can function as counter-conditioning, even with the alternative behavior having no relation to the issue prompting the fear. One qualification, however, is that it must often be an active behavior. If you are slowly exposing a dog to something they are scared of, telling them to just sit quietly will probably make things worse. However, playing a simple game or rolling for belly pets while exposed to mild fear will help dogs (or people, for that matter) to deal with the fear. The most common approach is simply having the dog walk in a safe direction.

The same applies to most people. Think back to the times you were nervous about something. Compare those times when you could only sit and wait, to the ones where you were actively doing something.

But, always remember the Second Rule. Take a look at Dr. Sophia Yin in Dominance. Her first example is counter-conditioning a dog who is aggressive for a toenail trim. The only thing I see wrong with her method is it violates the Second Rule. So, it will work on some dogs, but not others. She simply fails to note that there are other, equivalent methods of counter-conditioning that are more appropriate for some dogs. Research on the effect of “hope” in conditioning has also shown its advantage. Here, to get the treat, the dog must let you hold her paw and tap the nails. Then, you vary the time and frequency of giving the treat. If the “hope” becomes strong enough, it will win the conflict and allow you to trim the nails without the very careful timing that Dr. Yin describes. In some cases, it will also work when her approach fails.

And, in the case of abrupt-triggered anxiety aggression (quick attack when past a threshold), simple counter conditioning may not be possible. Instead, active redirection training is a good solution. Here it gets more complicated, as the dog (or cat) must be performing some learned and high-value activity at the time. In one case, the dog loves to tear into a certain toy, but is only allowed to do so while you are holding their paw and tapping the nails. Once this is well established, cutting the nails will only increase the intensity with which they tear into the toy. You have not stopped the anxiety that prompted the previous aggression but redirected it to an acceptable expression.

On the same topic, some dogs (and a larger number of cats) will enjoy your petting for a few minutes, then quite suddenly go to bite or claw you. Here, the simplest solution is often to stop your petting every minute or so, just letting your hand rest there for a bit, then resuming. With my last cat, the interval seems to vary quite a bit, so I taught her to instead take her paws and simply push my hand away. That worked for quite a while, then she found it not satisfying enough and she will now simply press her teeth against my hand. I don’t say anything or even pull away, but just stop all movement for a few seconds.

Another aspect is realizing why a dog is doing something. At the local dog park I see a dog who is often jumping up on people. His owner just yells at him and tells the people to just push him off. The dog, of course, immediately jumps back up. Here he’s looking for attention and play and just pushing him off is giving him both of them, so you’re reinforcing his bad behavior. Not quite what his owner had in mind.

Dogs and Time – Click

How fast is fast enough? Clicker training came from work in behavioral psychology several decades ago and about 1965 was used by Bob Bailey and others as a tool to help the dog relate a subsequent reward to a previous behavior, when it might be difficult to give the reward soon enough for the dog to relate them. This was later popularized about 1985 by Karen Prior and her school. Some books say the positive response to a dog’s behavior must be within 1/2 second, or two seconds, or varying other small numbers. But, my Second Rule also applies here. Depending on the dog, other unrelated activity that is happening, the distinction of the behavior (to the dog, of course), and other items, that time factor varies all over the place. While you should always try to keep it short, don’t ask the human experts how fast it needs to be. Instead, ask the dog. In general, if there are no other distractions, I’ve found five seconds to be fine with most. Having said that, I’ve seen a few that needed a much faster response. And don’t forget the dog who only gets rewarded after a five-minute sit/stay or completing a sequence of actions, and yet it all works.

A case at the other extreme is several high-apathy hoarder dogs I recently worked with. The action I wanted them to take was to allow me to leash them, then lead them outside, past a whole bunch of barking dogs in their cages. Arriving outside, they then had to get past benches and people, until finally getting to the walking paths where they could wander around and sniff at their own pace. Here, you have the “reward” applied several long minutes after the action. But, over a course of weeks, every one of them began to learn it.

Even further was a high-anxiety inbred hoarder dog who was afraid of everything but her shadow. Nobody could walk her or even get close. For about a month I had to slowly and carefully lasso her and patiently prod her out of the cage and onto a walk, then carefully unleash her with the dog snapping at me. She slowly grew to enjoy the walks. For months now I’ve been walking her, where I slowly walk around her run until she pauses, then slip the leash on and off we go. Returning, I show her my hand, she ducks her head, I loosen the leash and she slips out. Eventually, I’ll have time to take her further, but for now she is about the easiest dog to walk and she does enjoy it.

Going further, tests have been made on various training methods, studying their resistance to extinction. It was generally found that delayed and intermittent rewards make a trained behavior more permanent. Of course, that’s where you end the training, not start it.

The Stubborn Dog

Ever tell your dog to do something and have him maybe just stand there or perhaps look the other way? And find this happening with something that he’s done hundreds of times before? Or had the dog empty the wastebasket when you spent weeks teaching him about that issue months ago? Sure, we humans tend to anthropomorphize (attribute a human-only characteristic to something non-human) some of the dog’s behavior, ascribing it to all sorts of complex things that other people might do. But, dogs are thinking creatures (and higher mammals like us) where sometimes it’s just a matter of degree between anthropomorphizing and reality.

Here you might be dealing with a conflicted state. The dog remembers the wastebasket as being a lot of fun and that wastebasket is now right in front of him with you not around. That’s the here and now, and your training is long ago, so why not?

Or, that the dog is trying to modify things to make them more fun. So he could leave the wastebasket alone most of the time unless he sees you look at it then leave the room. He’s learned that that will invoke the strongest response from you.

Positive Reinforcement, Positive Punishment and Inhibition

From E. Kathy Meyer, AVSAB (American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior) president:

Behavior modification and training should focus on the scientifically sound approach of reinforcing desirable behaviors such as focusing on the owner and removing rewards for undesirable behaviors.

That sure sounds good, but think about it for just a minute. While removing rewards for undesirable behavior stops you from reinforcing it, that doesn’t remove the pleasure the dog gets from unraveling your roll of toilet paper. So, how would you apply positive reinforcement to stop something like that? In some cases, you can use positive reinforcement to increase the likelihood of a dog performing some action that precludes the undesired one. For a silly instance of that, teach your dog to always shut the bathroom door, which would keep him away from the toilet paper.

I’ve also heard others say that punishment is an ineffective way to teach behavior. Scientifically, those people are somewhat lacking, as if they were correct the dog species would have gone extinct many years ago. Consider a dog learning how to catch game or uncover some food. The required behavior here is reinforced by the reward and it may take them many attempts to learn how to do it well. But that’s fine and normal and they won’t starve from a few failed attempts. Now, consider the first time a dog meets a bear and is raked across his side with the bear’s claws. If the dog does not learn very quickly from that punishment, he may not survive a second encounter.

Between reward and punishment training, studies have shown that different portions of the brain are involved and that rapid learning from punishment is likely a survival characteristic. So, why not use it? For one thing, Rule Three says that we do use it to some degree. For undesired behavior you may tell your dog “no” and stop saying it when the behavior is not present, which is positive punishment. However, punishment alone has several drawbacks.

While simple to use for inhibiting a behavior, punishment is awkward to use for teaching or encouraging a behavior, just as positive reinforcement may be awkward for inhibiting a behavior. But with a combination of both, you can reduce one behavior while teaching and encouraging another to take its place. Where some people fail in this is in either using far too much punishment, not relating that punishment to the behavior, or not supplying an alternative behavior when needed.

Another drawback is ethical, and presented in Lindsay’s LIMA principal. Why cause pain or discomfort when it’s not necessary? So using the Least Intrusive and Minimally Aversive approach is more “humane”.

However, I’ll add to LIMA that the approach should be Appropriately Efficient. Say you’re working with dogs at a kill shelter and they’re headed for the kill list due to behavior issues. If for one dog you have a month to work with him, a gentle approach may be just fine. But if another may be killed in two days unless you can demonstrate enough improvement, a far more intrusive approach may be needed if it will be more efficient with this particular dog. In a third case, you have four weeks, but also two dozen dogs and your availability may be time-limited. Do you adhere to LIMA and perhaps save six dogs, or do whatever proves most efficient and perhaps save over a dozen?

There are some organization who claim to embrace LIMA, such as the Certification Council for Professional Dog Trainers. But you would find they have not only abbreviated the definition, but also added some of their own views. All of which is quite different from the original LIMA.

The intensity varies the impact

And, we must always apply the Third Rule. In Breeden’s mostly well presented Dog whispering in the 21st century he gives us:

Psychological stress is far more potent than physical harm (albeit physical harm always has a negative psychological by-product), and methods involving confrontation are dangerous in the response they can evoke. Behaviors included in confrontational methods are: leash corrections, muzzling, choke and prong collars, forced released of items from a dog’s mouth, alpha rolling, force downs, kneeing dogs in chest for jumping, hitting or kicking dogs, grabbing jowls or scruffs, dominance downs, neck jabs, shock collars, bark-activated shock collars, rubbing a dog’s nose in house accidents, yelling, “tsst” or “schhh”, stare down, water pistol or spray bottle, forced exposure, and growling at a dog. These methods produce aggressive responses from dogs as much as 43% of the time that they are employed by pet owners (Herron et al., 2009).

While some of his examples imply considerable pain or shock, others depend on the intensity and use. I have occasionally used a muzzle. I often use a water spray bottle, primarily when many other people have already desensitized the dog to voice. Neither one is used for very long, except that spray bottles are good (and safe) interrupters during play groups with shelter dogs. A sharp “tsst” as an interrupter or to provoke an attending response does not invoke an agonistic reply from the dog. I am often introducing new dogs here in a large run, and standing there with a water hose is often effective, and most times it is not necessary to squirt the dog, but just to aim near them. Finally, the cited study by Herron did not qualify the intensity, and their quoted 43% shown above was only for “hit or kick dog” with other results being lower.

As for his cited leash corrections, I’d love to see a real definition here. At one extreme, simply providing your dog with a restraining leash is in itself a leash correction. And when my dog wants to follow an interesting scent he gives me a brief tug on the leash, but I never respond aggressively to him!

Should You Stare Down Your Dog, and Other Confrontational Methods

This runs into a combination of the specific dog’s responses and the intensity of your approach. In all cases, the First Rule applies and determines what is appropriate. I have had dogs who often ignored your commands unless the intensity was high enough. Dogs where I started with by shouting, but a few weeks later could drop down to a whisper and they would respond. With a very scared dog, however, a shout is abusive and ineffective. With them I may start with only a whisper, and later progress to a normal tone of voice.

The effect of staring may also vary. With a display of stubbornness, a calm stare from a frozen position may be effective, but with a display of anxiety or agonistic behavior, a confrontational stare moves you in the wrong direction. Note that a calm stare is different from an intense one, with both dogs and people.

Following along these lines, a frozen position itself is a confrontational approach to a dog with poor impulse control. But, a far more effective approach than yelling and waving at him. The dog wants your active response to him, but he’s not going to get it until he behaves.

So, effective communication and understanding determine the answer for any particular context.

What Method Do I Suggest to Train a Dog?

I try not to do so. There are several approaches that are quite good, and may all work for you. For any particular approach, however, my answer is “yes, no and maybe”. With some dogs and issues positive reinforcement works quite well, but with some others (such as scared dogs) classical reward training is often far more efficient. This is where the “maybe” comes into it, as some approaches may be much more efficient than others. Looking around at courses for dog trainers, the only one I’ve found that covers this and all of what I consider to be the basics is the Academy for Dog Trainers created by Jean Donaldson. Take a look at their syllabus and you’ll see what I consider to be both basic and necessary to handle many of the issues.

Another factor also enters into this one. When I visit people having problems with their dog, the most difficult part is finding an approach that the people are both willing and able to use. Some people simply cannot effectively use certain approaches, and some methods may require more time than they have available. Often you need to make your best guess while watching them practice, then call in a few days to ask how things are going, now that both they and the dog have had some practice. So, what do the real experts do? They also start with their best guess, then adjust it, but often in only days, and sometimes only minutes.

Yet another factor that impacts a person’s success with any training approach is their reactions. A dog training book will typically give you a set of steps to follow, including how to reward the dog for a good response. However, exactly how you respond to hesitations and failures is more complex, and will often have a large impact. This is not only difficult to describe, but here you tend to follow your natural habit patterns, developed over many years, and changing them is very difficult. Yet another reason why we often need to experiment with different techniques.

I recall one woman who had trained her dog to take treats but still had an issue with him appearing to snap at her hand. Watching, she seemed to be doing everything right, except at the instant she told him to take the treat she would pull back her hand so he’d have to lunge forward. Until I pointed this out, she had never noticed herself doing it, and that resolved the issue.

And what’s the right word to use for a command, many have asked? If this is an immediate or emergency command, there is always something that you would naturally say in this situation, so use that instead of trying to remember something new. In general, try to use your natural responses.

Positive Aggression

According to the Journal of Applied Animal Behavior (2009), if you’re aggressive to your dog, your dog will be aggressive, too. Well, here comes my Third Rule again.

Now, aggression itself has a slippery definition, especially as some aggressive displays in dogs are intended to actually prevent physical aggression. In ethology, a better term is agonistic behavior which is any social behavior only related to fighting, which includes threats, retreats, and conciliation. Often in dog playgroups we see one dog issue a forceful correction, where he growls and snaps at another dog but then stops, indicating he may not continue. The other dog will often turn his body in another direction and look away, indicating he is deferring to the first dog. That agonistic behavior tends to prevent physical aggression.

Years ago I adopted a “problem” dog who used to jump up on people and nip them hard enough to cause a bruise. He has a strong tendency to jump up and negation wasn’t effective, so I’m teaching him to jump up on command (which was very easy) and then to go off on command (slowly getting there). That’s the first step to getting a handle on his jumping behavior, and it allows you to then teach him with much higher repetition and on your schedule, not his, while also better communicating with him.

The training games

Similarly, I taught that dog tug-of-war. He really loves the game and from it he’s learning better tooth and mouth control. He will also go from a full-aggressive pose to a relaxed sit in under four seconds, and has to do that several times each session. That same command was then generalized for when he displays agonistic behavior with another dog, giving me a positive handle on the situation, much more effective than “no” or “sit”.

Yes, this is a game. But, more importantly, it is a structured and controlled technique, while still being aggressive. As a result, the dog is now much less aggressive with people. He has rules, and he really likes the results from the rules.

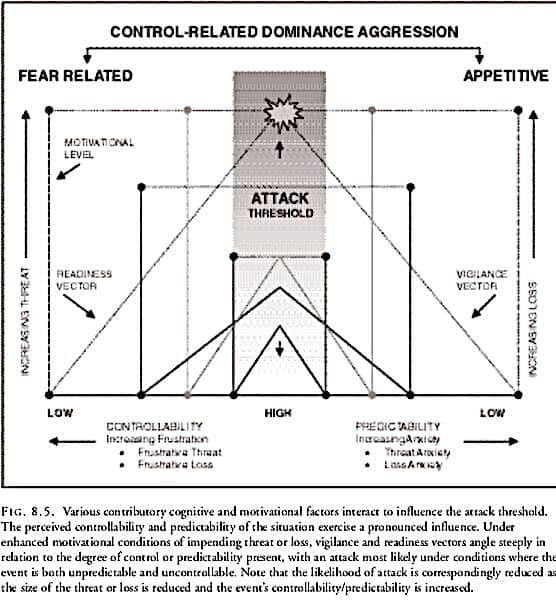

Another aspect of aggression can be found in Lindsay’s Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, Volume 2, on page 256. Here he shows a threshold chart that indicates the likelihood of an attack and relates that to both the size of the threat and the event’s controllability/predictability. It is by avoiding this threshold that I am able to work with many aggressive dogs.

Where to find Help

This is certainly the hardest question and I don’t have any good answers. Over the decades I must have interviewed thousands of people for technical positions, and have found several things useful. First, the extremes are easy and quick to identify. Both the very skillful and knowledgeable people, and the ignorant ones can be quickly assessed. The large middle area, however, is much harder to quantify. Second, I care less about your successes than your problems and failures. How you overcame problems and why you failed provides a great deal more detail about you. Anybody can claim another’s success, but only the people involved know the details of problems and failures. Finally, sadly there is often little correlation between the degrees and certificates, and real ability. Too often ten years’ experience is one year, just repeated ten times.

The same applies to dog trainers and behaviorists. Many have all those letters after their names, but are woefully ignorant. I spoke earlier about Lindsay’s LIMA principal then mentioned that to a certified “positive” dog trainer. She replied that she might try it if positive methods did not work. I tried explaining that LIMA is a philosophy that does not specify an approach but only the criteria for selecting one, but she was lost on this distinction, nor did she ever look at any references I sent her.

Another trainer related a previous issue with an aggressive dog who threatened and then attacked. I tried to explain that her response had likely caused the issue and what she should have done instead and that my opinion can be supported by literature and research. Her response was to simply ask her “mentor”, giving her understanding of what I said and being told that her mentor knew of nobody using that approach. Here, all that I had really explained was how to not threaten a scared dog!

The Karen Pryor Academy seems to be a very popular approach. Yet their course descriptions seem rather dumbed-down and very limited. None of the graduates I’ve met have ever been able to give a technical description of what they actually do, nor understand the limitations of some approaches. They claim an innovative approach but show nothing to support that. They tell me how great clicker training is, but when I state that it is a form of operant or instrumental conditioning that utilizes positive reinforcement with token replacement, they have no idea what I just said or when it is not an appropriate or efficient approach. If you don’t understand the limits, then you cannot truly know the approach.

Beware the guarantee

Then we have A Fresh Perspective Dog Training. They claim:

- They have been using their proprietary p​ositive-reinforcement methods to work with dogs for almost 10 years.

- They also have developed a training program certifying others to train with their methods.

- The program also prepares the student to manage behavioral rehabilitation for issues with dogs in homes.

My goodness, but positive reinforcement became well studied in the 1950s and a great deal more about canines has been learned since then. Whenever I see anybody claiming secrets or proprietary methods, a red flag immediately pops up. Previously, their web site had shown their past successes, including one at a local shelter. However, that same shelter had a far different story about their time there. Checking with local dog rescues, I heard the same story about them and at a local dog park I met a person having some trouble with her dog who had poor impulse control. Some time later, she told me that she had used their services. That they came in very assertive, with a description that sounds like a Cesar Milan approach. She saw that they could control her dog, but that there was no way she could ever use that approach. At that point she gave up, and had the dog put down.

As I said earlier, the hardest part of helping someone with a dog problem is finding an efficient method which the person is both willing and able to use. There is never only one answer, and anybody who insists that you must follow a single approach is somebody to immediately walk away from. Yes, their methods will sometimes work. But nearly any approach will sometimes work, though often at considerable cost.

Few schools cover more than the basics

At the other extreme, I spoke about the Academy for Dog Trainers. Their syllabus gives a detailed description using proper and meaningful terminology. If I were to start my own course for dog trainers, it would be very close to what they supply. Unfortunately, real learning requires real work, including reading and research, and many will not go that route. If you do happen upon any of their graduates, I feel you’ll have a much better chance of finding a true professional to help you.

Some universities do offer good courses, but it seems rare to find people who’ve taken them. And over the years I’ve worked with many people having advanced degrees whose only skills were in passing tests. References are often of little value as they are only from satisfied customers, and many of them may not understand what could have been done better or easier. It’s often much better to contact your local shelters and rescues and ask for their opinion on local dog trainers and behaviorists.

Now, for general and simple obedience training, the results were different. I’ve monitored several local dog trainers and found most of their methods reasonable, and they did well in imparting basic information to new dog owners. They handled simple problems well, had reasonable charges, and were available for advice if issues arose. None of them claimed any proprietary methods or secrets.