Table of Contents

The Most Important Training Lessons

In canine rehabilitation, we always start with deference and relaxation, with a focus on Attending and Orienting responses. We don’t move forward until this is completed. No matter what type of training you are using, the following are needed:

- Attending response – The dog must pay attention to you.

- Orienting response – To lay down “there”, he needs to know where “there” is.

- Relaxation – If he constantly fidgets after a few seconds, training is an uphill battle.

- Deference – He learns to defer to what you want.

Without finishing these first, it’s a bit painful watching people try retrieval or go-to-place (lay on a mat) when they keep losing the dog’s attention, but have to break out the smelly hot dogs just to keep him looking at them. Perhaps because those 4 items seem a bit boring, most trainers seem to focus on feeding tons of treats instead.

It’s interesting that I find some aspects of this in the first few lessons from many training classes. But they always seem to go onward before it’s finished, because sit/stay/come/retrieval/leave-it/park-it/shake/roll and such seem to be more useful, or at least more interesting.

And this is even more apparent in leash training, with some trainers using tubes of soft food held by their side for an almost constant supply of treats. Yet even with that, some dogs are still resistant. But not if those initial lessons are well learned.

I’ve written elsewhere here that I typically use few treats when training a dog. They are neither needed, nor do they always make things go any faster. Instead, those four items make all the difference. Do you clicker train, use lure-reward, positive reinforcement, classical conditioning, or the Magic Foobah approach? No matter which, as these items are common to them all.

Karen Overall – Protocol for Deference

Karen Overall – Protocol for Relaxation

Is Partial Science still Science?

With the very common issue of helping a scared dog, are we really using science?

So many times I hear about the Magic Wand of Desensitization, and how it’s so very based on science. How its gentle exposure to what they fear will solve the issue. But let’s start with an analogy here for an animal (like us) who is scared of something. Say you don’t know how to swim and are afraid of the water. Here, there are four possible approaches:

- Avoid the water, period.

- I keep throwing you in the water.

- I feed you chocolate as we approach the pool until your feet are in the water, then I wait and see.

- I teach you how to swim (chocolate still allowed).

And many dog trainers seem to use only C) and stop there, hoping the dog will take it further. Which many will, eventually, but some will never manage it.

Now, when you’re scared of an unfamiliar situation we actually have the following components:

- Understand that what you are seeing isn’t so bad and can be approached.

- Become familiar with watching others and what may happen.

- Start interacting based on your prior and current experiences, watching results to learn the rules.

- Adjust your behavior from responses and results.

- Determine how much you like or dislike this situation.

Now, dogs are often pretty adaptable. After desensitization from C) helps them through 1 & 2 above, they will often manage the other steps on their own. Sometimes pretty quickly, but other cases can take weeks or months of trying.

For a case study, a shelter dog had a problem with becoming aggressive when meeting new dogs, and the shelter gave up on desensitization after over two months of trying. It was during step #3 that she became fear aggressive, and they didn’t help that. After a week of teaching her commands that affected steps 3 & 4 above, we tried again, starting with selected new dogs. First, she learned fear-lessening behaviors to use when she was afraid, behaviors that let her calm down instead of starting a fight. In about two weeks or so, she had met over 60 new dogs, gathering enough experience to guide her in the future, and was soon adopted. As an aside, no treats were given (or needed) during this. This dog learned to calm herself down without the token chocolate (high-value treats).

So, while desensitization is useful, it’s often presented by many dog trainers as the entire story. I’d suspect this began as a simplification, to make it easier to teach dog owners, since desensitization by itself will often work and the steps for that are much easier to learn than the following ones. However, many dog trainers seem to stop after they learn simple “recipes” for problems, rather then learning more and understanding the entire process.

The Mantra of Positive Reinforcement (+R)

Even past the clicker training claims and looking at other dog training techniques, I see and hear so many claims that the magic wand of positive reinforcement (+R) can cure all ills. A few sites even give you a correct definition of +R, then ignore that and spew out all sorts of claims. Since there are no real magic wands and since no key fits all locks, we know there must be some limitations to +R, but they are never discussed. With some Dog Trainers, even bringing up that question is anathema to them.

In this imperfect world, we know something is wrong with this, but so very many people just want to hear good, nice, and simple answers. Positive reinforcement is one specific type of what is called operant conditioning, but another general type called classical (Pavlovian) conditioning also exists and is often effective. However, going through the course descriptions of many dog training schools, I found only a single school that not only mentions classical but even gives you the criteria for choosing which is more likely to be effective. That’s at Jean Donaldson’s The Academy for Dog Trainers.

Now, operant conditioning includes four (and sometimes five) different forms:

- Positive reinforcement

- Negative reinforcement

- Positive punishment

- Negative punishment

And now this explanation gets a bit harder to follow, as otherwise familiar terms get used in a different manner.

Of those four, positive reinforcement occurs when an event or other stimulus is presented as a consequence of a behavior, and the likelihood of that behavior repeating in a similar environment then increases. So if the dog realizes that running over to sit on his mat every time the doorbell rings will get him a tasty treat, he may be more likely to repeat this when he hears the bell. But, note that +R is not really a method to use, but only something you try to achieve.

The other operant forms are similarly defined, with positive just meaning that something is added (like the treat), and negative that something is taken away. And reinforcement means the likelihood of a repetition increases, and punishment that it decreases.

Some definitions use words like desirable for positive and aversive for things with punishment, but neither description is really needed. Things used for each one can be rather neutral, or even slightly in the other direction. It’s all in if these are added or removed, and if that causes the behavior to be more or less likely. However, many dog trainers do seem to miss that point, which is covered more in the next section.

Skipping over the remaining details for now, a few dog training sites actually dare to say they may slightly and occasionally also use negative punishment, but most either don’t understand what it means or are simply scared to use anything containing the word punishment. Nobody, but nobody it seems would ever condone the use of positive punishment in dog training. But, if your dog does something less because you’ve told him no after each time, then you have used positive punishment. So their focus seems less about the science, and more on advertising.

Say that somebody repeatedly and insistently tells a dog to sit, while the dog tries different behaviors to try and make them stop the annoying repeating, which only happens when they do sit. If doing this many times then increased the likelihood that they would sit much sooner when given that command, you have used negative reinforcement.

Next, just go back and look again at just those two examples. If you were to check Wikipedia, both examples here would be correct. However, my examples of positive punishment and negative reinforcement are deliberately sounding very close to each other. And the only distinguishing difference is that the former results in a decrease of the behavior, while the latter is an increase. Yet, the use of the word punishment in one case has so many allegedly knowledgeable dog trainers refusing to use it.

All the operant types are there

In the real world, very often all the available types of operant conditioning are actually used. It’s far more a question of the specific use, intensity, and frequency of each type, often tending to favor positive reinforcement as the focus.

Some dog trainers respond that it’s all too confusing to people, so they simplify. Or it’s just more detail than is needed. Or, perhaps, that they themselves don’t really understand it? Yet, it’s all found in Wikipedia under Operant Conditioning and other related areas.

From my perspective, +R is just one focus of various approaches that can be appropriately used. For some cases, I may start with Ian Dunbar’s Lure-Reward approach. This often begins with classical reward conditioning, then transitions towards +R, perhaps giving you the best of both, often with faster results.

And teaching a dog inhibition is a big problem for +R. After all, giving a reward for a dog not doing something is rather difficult for the dog to associate and then create a strong motivation. If the dog keeps barking, do you then give him a treat when he stops and is silent? Might not the dog then learn to bark whenever he wants a treat? More often I see them prompting the dog to perform some distracting behavior, then reward that. But if the dog doesn’t connect all of those dots, you won’t really get very far, and can worsen the situation.

Not only is it awkward to use only positive reinforcement for this, but it’s also nearly impossible to have only +R in many compound training scenarios.

For the most part, I actively use all four types of operant conditioning, but with neither food treats nor strong aversives. Much of what a dog would learn without people around is done with self or auto +R, where it’s the result of the dog’s behavior that makes it more likely to happen again. A focus on communication and compassionate teaching can often direct that learning. Since the behavior is never dependent on treats, it also happens when you’re not around to give them. Could you also use treats as rewards? Sure, but a few more detail will be added to that later on.

The One-Word Rules

- If your dog is fearful, do this but don’t do that.

- If your dog is aggressive, do this but don’t do that.

…on and on it goes.

Perhaps the majority of scared or fearful dogs I see simply don’t have the experience and skills to know how to handle many situations. While some others may have a mild anxiety issue or simply personalities that will always be shy, and still others may have some degree of a general anxiety disorder, at times very severe. But they’re not all the same.

Similarly with aggressive dogs, there are a whole bunch of reasons and components that may be involved. Some can be and always will be dangerous in certain situations, but there are over a dozen different types of aggression. And nothing says there must only be a single root issue.

While some issues can be rather complex and difficult to manage, most are much easier. However, very few can ever be fully described in a single word. So why do so many so-called experts give these hard rules? Some say there’s limited room in a short article, but is that really any excuse for saying something that will often be wrong, without mentioning that there’s more to this? And I’ve seen entire books with the same problem, with far more space dedicated to specific solution exercises than any attempt to really understand the problem you’re trying to solve.

The queen of one-word rules

ARE DOMESTIC DOGS LOSING THE ABILITY TO GET ALONG WITH EACH OTHER?

An easy way to find examples of this today may be to look for Victoria Stilwell or her students. This item above starts as an interesting article, comparing how well those Village Dogs live comfortably in a social group, against many of our pets who seem scared or aggressive with other dogs. Stilwell then discusses some likely reasons and causes for this, starting with some general advice. But while she quotes Dr. Ian Dunbar and ethologist Mark Bekoff, we can see she has some conclusions in her dog park comments. Ones that the Village Dogs probably wouldn’t agree with.

More and more young dogs become unruly and socially awkward. Some become bullies and others are just downright dangerous. A few of these dogs end up being “socialized” in our dog parks. It’s a dog’s natural instinct to avoid dogs that are threatening, but how can a frightened dog avoid an out of control “canine missile” that is barreling towards them across an enclosed park? It is rare for either of the owners to intervene when this happens.

Victoria Stilwell

First, many dog parks may be ½ acre or more in size. Is she implying the dog may be chased that far? If so, wouldn’t that also happen with the Village Dogs she speaks about? And if the regulars at my local dog park see an out of control canine missile, several people will jump up at once. And the regular dogs are used to newbies coming in and give them some space after a few minutes. But for most cases, her quote from Mark Bekoff actually applies:

Animals at play are constantly working to understand and follow the rules and to communicate their intentions to play fairly. They fine-tune their behavior on the run, carefully monitoring the behavior of their play partners and paying close attention to infractions of the agreed-upon rules. Four basic aspects of fair play in animals are: Ask first, be honest, follow the rules, and admit when you’re wrong. When the rules of play are violated, and when fairness breaks down, so does play.

Mark Bekoff

And that’s exactly what happens most of the time at the dog park, so that much of Stilwell’s advice may conflict with her own references to experts, and she never seems to notice that.

Desensitization and Sensitization

From Wikipedia,

Desensitization is defined as the diminished emotional responsiveness to a negative or aversive stimulus after repeated exposure to it.

Which is often used with dogs who are scared of something. Note that the aversive stimulus may actually be something otherwise thought of as good, but it’s aversive to a dog who doesn’t understand it.

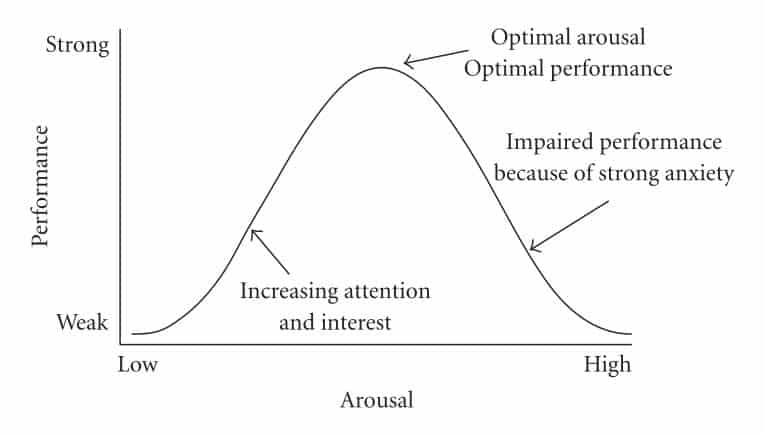

One mistake many trainers make is in simply telling people during desensitization to keep the dog under threshold, but never explaining what threshold really means. Unless the dog does feel some arousal, there is nothing for them to learn from this. But if the dog is too scared, they may panic or become uncontrollable, so no learning there either. And since different dogs react differently, how does one know what’s enough?

The answer is a practical one. I first teach the dog an alternate behavior that they find calming. One that you want them to do when they get scared (e.g. back up and go behind me), then keep taking them forward until they don’t listen to that anymore, or are unable to visibly calm (recover) quickly (< 20s) after executing that behavior. Then you know that you’ve gone just a little too far and can backup up. Most times, this initial point is found in just a few seconds, then continually adjusted.

So, why not just stay way below the threshold all the time? The answer has to do with learning efficiency, and if you want to complete this in only weeks, or to take many months. From psychology, this relates to the Yerkes-Dodson Law, showing that performance increases with arousal, but only up to a point, then decreases.

So at the low end here, the dog is so far removed that he’s not even paying attention to the problem area, and it is obvious there will be little or no learning, just like you can’t teach a dog commands unless he pays attention to you.

Traumatic Learning

But I’ve often heard the dangers of the high end, where going above threshold even once may need months of work to correct. For that to happen, a survival process called traumatic learning would have to kick in. That’s what happens if a dog gets clawed from trying to steal a bear’s food, where he had better learn that the first time, or the next may be his last. But that, of necessity, has a very high threshold. Otherwise, the first time you brought out a young dog who became scared of a car driving by, he would become immediately terrified of cars and everything else on the road that scared him. Yet we know that this doesn’t often happen.

Aiming for the middle

Avoiding both of those extremes I start with brief intervals and aim for a recovery time under 20 seconds. If way under, I’ll increase either the intensity or the duration a bit. If longer, we back things down. And, while you’re likely to initially see some improvement, the recovery time will eventually start to lengthen as he tires, and that’s the signal to quit for now. Here, recovery time is something that you can measure, instead of some subjective opinion.

Therefore, time duration and intensity do have an effect. If the person is not aware of the dog’s anxiety and allows it to continue very high for some time, that may have a moderately strong effect that we’d like to avoid. And for that reason, we advise people to be cautious, even though it may lengthen the process. But, why not give them the working definition I noted above?

Scared young Bono was reactive to all people and dogs until Bandi gave him the calm and security he needed to start learning. He would be prompted to go out and explore, then run back to Bandi when it became too much.

And it also works the other way

The definition I gave above seems based on a negative or aversive stimulus. But I’ve also had dogs who were so excited at some game or other activity that they loved that it was difficult to train them, and even after they would forget their training until they settled down. Well, it turns out an analogous desensitization approach works just fine in those cases.

The Dangers of Danger

Some time ago I read a warning, posted by a woman representing herself as not only a very experienced Dog Trainer, but also a behaviorist. When leaving the house, she was accustomed to letting her dog walk free to the car. One day, he saw another dog across the street, ran towards him, and was struck and killed by a passing car. This trainer said she never realized this might happen, as her dog had been through retrieval training. So she crossed this off as a totally unpredictable accident and implored all other people to never take this chance, no matter how your dog has been trained.

Yet, I continue to do this, all the time. That my dog has had retrieval training has no significance here, as she completely failed to understand. Unlike her dog, mine has had impulse control conditioning using representative stimuli. There, he needed to both sit and stand still while watching moving objects that included: people, cars, dogs, cats, and even a rabbit. Then, he needed to be actively moving towards an object, and stop and return on command. That part is very important. The final step is the dog energetically engaged in activities he really enjoys, then stopping on cue. For my guy that included tug-of-war and running full-speed after a ball or treat. At this point, he often walks off-leash past a variety of dogs and some cats, without any issues. If he really wants to go and see one, he’ll signal me first, as we have also established the behaviors he will use in those situations.

Of course, this does not say that he won’t run after a pheasant, but he’d be likely to hesitate and I’ve never seen one on my street. And I’ll give special thanks here to the unexpected rabbit who assisted in this training.

The point here is the lack of very basic knowledge and even common sense that the Dog Trainer demonstrated, and that she certainly didn’t learn anything from her mistake. No matter how careful you are, sooner or later that dog may break free, and you need to have at least some control there, rather than ducking your head in the sand, which is what she advised.

The Absolute Guarantee

In these days of advertising hype, we assume that most everybody claims to be more than they are. Here I picked a dog trainer who goes a bit further than most, and where I have tracked some of his activities over several years.

I saw that this local trainer has restarted his dog training business again. It was apparently closed for a while, when he took over management of a local dog shelter. A brief period of only a few months, before they abruptly parted ways. There are many good techniques for obedience training and often too little detail is given by a dog trainer to understand what they propose. Instead, as my area focuses on behavior issues, I look at the promises they are making in that area.

“In all cases, behavioral issues can be successfully addressed with a proper understanding of why issues arise and how they are reinforced.”

With that statement, they are implying that they possess that capability. Which means that a great deal of behavior research still being conducted on dogs is not needed anymore, since they can handle all cases.

“This can be anything , from dealing with a hyper-active puppy to rehabilitating severe fear and aggressive behavior.”

Severe fear? There does exist something called Generalized Anxiety Disorder, which often requires months or years of effort, often with supporting medication. There are active dogs with poor impulse control, but there are also dogs with hyperkinesis, which is far different. As fear and aggression are the two most common complaints, there are many contributing factors that are poorly understood even by true experts.

I do recall, several years ago, reaching one of his clients too late to help. This was just an active young dog with poor impulse control and no training. In just one session he had both controlled the dog (with intimidation) and completely convinced the owner that she would never be able to do that. She then took the dog to her vet with the issue, was told that many pits become like that at 2-3 years of age, and the dog was killed.

“An initial session lasts 3-4 hours and will I include a complete solution for the dog’s issues. We recommend a follow up session 2-3 weeks after that to help you firm up your skills and deal with any new issues that may have arisen. The follow-up session lasts 2-3 hours.”

Well, I guess that I’ve been doing it wrong. While I budget 3 days for a full assessment and treatment plan for serious pathological behavioral issues, he can do this in only 4 hours. Yes, the vast majority of dog behavior issues are rather mild and relatively easy to correct, and often the largest effort is needed in changing the owner’s behavior. But, truly severe fear and aggression are certainly not in this category. Nor, for even the easier cases, can many dog owners learn the needed skills and behavior changes in only two sessions, no matter how long these sessions are.

And he goes even further, in offering his own Trainer Certification Program for Dog Trainers, using his unique and secret methods. A full year of instruction is provided, which is then accomplished in 270 hours (about 34 8-hour days). To be fair, this includes information on service dogs and PTSD assistance, which may be of value but cannot be assessed from the available information. However, just his claims for resolving behavioral pathologies alone would require far more than the total time available here.

Dogs Generally Don’t Generalize, in General

So many times I’ve heard: If you teach a dog something in the house, he may not understand it outside, as dogs do not generalize. So you have to at least partly train them for each different situation.

In reality, if I teach a typical dog to sit in the living room, I might expect something like:

- 98% to sit in the bedroom

- 94% to sit in the kitchen

- 88% to sit in the patio

- 79% to sit in the dog run

- 75% to sit while on a walk

- 10% to sit at the dog park

Well, far from perfect, but a very far cry from what the dog trainer said. And the issue at the dog park is less that he didn’t understand, but more that he’s less motivated due to the excitement and distractions there.

Now, of course dogs cannot generalize as well as (most) people. But if dogs couldn’t generalize at all, then (think about this!) the canine species would have gone extinct long ago.

Consider now that all training involves three components:

- Comprehension (understanding)

- Motivation (they want to do it more than distracting activities)

- Persistence (they do it repeatedly)

There surely are cases where, in another context, the dog really doesn’t understand what you’re asking him to do. However, the more common issue is in motivation. This applies both to a possible reward being given when you’re elsewhere, and also to the value of that reward against the fun of playing with other dogs at the park. In a quiet living room, a piece of kibble is enough. But maybe not at the dog park when his friends are calling.

Motivation, et. al.

While training consists of comprehension, motivation, and persistence, sometimes we just get stuck on the motivation part. When a dog wants to perform some particular behavior but you reward him for a different behavior, sometimes it’s just not enough. Try higher value food rewards? Maybe, or not. If a dog is jumping on people to get attention, you have some control over his objective (you) and can teach an alternate behavior that satisfies him. You can even teach him to jump up on command, allowing you more control and higher repetitions. But say the dog just loves to chase after things while barking and jumping. Let’s say he’s mostly fine in the dog run or at the dog park, except when something unusual like a skateboard, bicycle, or motorcycle goes by. He then starts running along the fence by the jogger, barking, and jumping.

So you teach him that you don’t like this. Perhaps he’ll get a reward if he doesn’t do it. But you can’t be there with a reward every time, and maybe his hope of getting a possible reward isn’t enough against the impulse to run and bark. However, he still may learn enough that, if you even calmly walk over near him, he’ll quiet down without a word spoken. But then you walk away and the barking starts. Sure, I can then call him to me to interrupt the behavior, but I can’t do that all the time, or when I’m not there.

And neither your corrections nor an ultrasonic collar may be enough to stop him if you’re not close because he simply enjoys the behavior too much. Other than by using the collar, there’s no way to always correct him, and even the collar may not be enough. Nor is there any satisfying alternate and conflicting behavior you can offer to take its place. Under these conditions, all types of operant and classical conditioning may fail. Perhaps a greater intensity may have an effect, but even hitting him with water from a hose may not be consistent enough to do so, and that’s bordering on what we would typically call abuse.

Over time and age the dog may settle down, which may take a very long time. But the point here is that, where the dog has a strong internal motivation and your resources and ability to control the situation are limited, you may fail.

Pieces to put together

Behaviorally, the best approach would be to first leash train the dog, then to take him jogging with you. Then teach acceptable behavior while you jog next to or approach other joggers. Then with kids on skateboards, then motorcycles. With this approach you have him under your direct control the entire time, with enough repetition, and he gets to do some of the chasing he wants, but in a good way. He becomes more familiar with those situations and less impulsive. Of course, it’s difficult to arrange for enough kids on skateboards, or motorcycles going by. And if you have a bad foot and can’t jog far, that adds to the problem. And while the noisy skateboard is typically far more enticing than the jogger, I’m a bit old to learn that skill myself.

When the weather warms up, we’ll start with some walks near joggers. Then spend some time slowly getting closer to a nearby skateboard park. Perhaps visiting a motorcycle dealership so he can become familiar with some quiet machines first. But dozens of trips will likely be needed.

With kids or another person at home, you could enlist their help. But, lacking the resources, sometimes effective counter conditioning is difficult to achieve. And, even after he becomes perfectly well behaved while passing them when on a leash, he may still run a fence and bark at them, just because it’s fun and nothing you’ve done has changed that.

Communication, et. al.

Earlier, I listed the three components of dog training. We’ve just spoken about motivation, and that seems to be the primary focus of many dog trainers. However, for people having initial difficulty in training dogs, perhaps the single, biggest issue I’ve seen is in communication.

Let’s think for a moment, of what typically happens with two people who speak different languages when one person finds out that another person didn’t understand what he said. If it was a simple statement, he will likely repeat it. If no joy there, then another repetition, speaking slower and louder. Eventually yelling it very quickly in frustration.

And, we often see pretty much the same when training a dog. Following a very detailed and structured training plan can help, as it guides you into different things to try. However, many trainers only give a single path, with simple instructions and a demonstration, and wait to see what happens. This is somewhat understandable, as many people have difficulty with very detailed instructions for something they are not familiar with.

At the start, I spoke of the four most important training lessons. Another good reason to start with these is to build a foundation for communication with the dog. I usually follow those first lessons with whatever the dog will learn the easiest. I may try a few dozen very simple things, but only spend time on those where I see a rapid response. If you relate this to learning another language, I’m trying to build up the joint vocabulary between me and the dog, which will make things far easier as we progress to more complex sentences.

Comparing the two approaches, starting with fundamentals may take much longer to reach what many consider basic training. But this will then progress faster. You will find the basic skills are more solid, and the behaviors are less disrupted by nearby distractions.

But even on single behaviors or commands, I see people becoming quite frustrated, as the dog doesn’t understand their words, but does respond to their body language in trying to either get away, or to focus on some other activity so they can try to ignore the confusion. And after a while of repeating this, the dog has decided on his avoidance response, and this training attempt becomes less and less likely to succeed.

Once the dog has gotten used to his alternate responses, it become far more difficult to change them. It is often better to ignore them for the moment, and to move back to the basics, where you can start building up communication and understanding for small things that you can then start putting together.

Schedules of Reinforcement

Most modern dog training has its roots in Behavioral Psychology, with B. F. Skinner being one of the best-known founders of that approach. This includes such approaches as positive reinforcement with token replacement, one form of which we currently call Clicker Training.

It also includes an entire book on Skinner’s Schedules of Reinforcement, which gives rules for when and how the behavior should be reinforced (often rewarded) for best learning and maintenance. But, reading from a clicker training expert on recall training I see:

“When you’re training, remember to give a super-good reinforcement EVERY time you call your dog.”

And the emphasis is on the immediate click, and the treat as soon after as possible.

While they’re first learning, sure. But once they’ve learned a bit I move to what are called ratio and interval schedules and spend far more time with those than trying to fatten up the dog. In Steven Lindsay’s classic Handbook of Applied Dog Behavior and Training, he mentions and references research that has shown that the use of these schedules with dogs strengthens the behavior and makes it more resistant to extinction.

However, the most I’ve heard some dog trainers say is to slowly (or rapidly) wean the dog off the treats, but only after they perform the behavior quickly and repeatedly. But that’s part of the purpose of using Schedules of Reinforcement. The actual research here has for several decades indicated the advantages of that approach, but very few Dog Trainers have caught up with this.

The Bottomless Bag of Treats

While the clicker trainers seem to be the worst, I see most dog trainers carrying these big pouches of treats everywhere, and supplement them with supplies of sliced hot dogs and other similar stuff. Some say if the dog won’t do something, go for higher value treats. Others say to always start with the tastiest stuff, then slowly wean them down to simpler treats.

At one clicker training class, I saw one dog learn that, whenever she wanted a treat, she could simply walk over to her person and sit. Her owner then immediately did a click, then gave her a treat. The trainer thought that was very good, completely missing the lack of an antecedent (prompt or cue) from the owner, which means that the dog was now in control (her sit was the cue) and she was training the person instead. Yet, this was a certified trainer, working at a large, local humane society group, and one which carefully screened all of their instructors for knowledge and competence.

On the other hand, I mostly use treats to train for just a few specific things with dogs. One is teaching them to gently take a treat from a person, using good mouth control even if the treat is held between fingers or buried in the hand. The second activity is taking a treat while next to another dog, or letting the other dog take the treat. Finally, learning to avoid lunging or snapping for a treat that is moving or dropped on the floor. I don’t think I could do any of these without using treats.

But, is my dog training really that odd? Many of these dog trainers were APDT Certified (Association of Professional Dog Trainers). One of the APDT founders was Dr. Ian Dunbar. I recall him writing that the main advantage of all those treats is that they are easier for people to learn to use. That he doesn’t use many treats in training, and that his wife is much better than he is, and uses even less.

And few if any of those dog trainers seem to have an answer to some of the scared dogs I work with. Using higher value treats? Not if they’re too scared. And then there were two ferals I had who would not eat with a human in sight, and toys were only things to steal away and hide.

Fortunately, the majority of dogs are very easy to work with, being very flexible and accommodating. Many different training protocols will work, often with different times and efforts needed, but they do work. And teaching people how to properly use treats in training can often be successful. Remember, the treats are not simply a reward, but also an often effective way of telling the dog that you liked what he just did. An often needed communications component to the training, if used properly so that the dog associates the treat with the behavior.

Reinforcement, Punishment and Interrupters

I’ll start by looking at two punishment definitions. From Wikipedia we see:

“Punishment is the authoritative imposition of an undesirable or unpleasant outcome upon a group or individual, in response to a particular action or behavior that is deemed unacceptable or threatening to a norm.”

Which is fine for most human interactions, but most dog training is based on Behavioral Psychology, and again from Wikipedia we now see:

“In operant conditioning, punishment is any change in a human or animal’s surroundings that occurs after a given behavior or response which reduces the likelihood of that behavior occurring again in the future. As with reinforcement, it is the behavior, not the animal, that is punished. Whether a change is or is not punishing is only known by its effect on the rate of the behavior, not by any “hostile” or aversive features of the change.”

Note that while the first one is unpleasant, the definition we use in dog training has nothing to do with that, and could even be giving the dog some treats, as only the behavior is punished. Now let’s look at reinforcement, again from Wikipedia:

“In behavioral psychology, reinforcement is a consequence that will strengthen an organism’s future behavior whenever that behavior is preceded by a specific antecedent stimulus.”

So both reinforcement and punishment relate to consequences that change the future probability of a behavior, with the only difference being that reinforcement is connected to an antecedent (i.e. prompt, cue ). From here we could discuss positive/negative reinforcement/punishment, then into sub-classes of each, such as positive reinforcement with token replacement, often done with a clicker. But just that the variations exist is enough to know for now.

Now if we look back at my first topic, you’ll see that the single most important item is the Attending Response. That if the dog is busy with something else, you may just get ignored. If a dog is doing something bad or just busy elsewhere, an Interrupter may be used to very briefly stop that behavior and get his attention, just for half a second. That could be just the dog’s name, but early in training something stronger is often needed.

How to interrupt

Two dogs were starting to fight at the dog park. I walked over, loudly clapped my hands above their heads, and they broke apart for a second, then just walked away. At the shelter dog playgroup, one dog is ignoring another’s signals to back away, and a water squirt in front of his face interrupts his behavior, without disturbing the others around. Now, if either action was used repeatedly and solely, with accurate timing, it might tend to reduce that behavior and therefore become a punishment. But, instead of that, as soon as you have interrupted the undesired behavior the dog is then prompted for an alternate behavior, which is then rewarded, putting you instead under the mantra of Positive Reinforcement.

Some people reject Interrupters and Punishment, claiming that aversives are not necessary. First, if you read again the definition of operant Punishment, you can see that aversives are not always needed. And for a trained dog, an Interrupter might be nothing more than speaking his name, which would only be aversive if you shouted in a nasty voice (or, he doesn’t like his name?). But both the clapped hands and squirt bottle above were aversive (as is a sharp “no”). However, they were the minimally practical aversives to efficiently interrupt the dog’s behavior. The owner who repeatedly shouts “NO NO NO NO” at their dog or keeps pulling on the leash is more likely using too aversive an approach, as compared to these.

Likely too aversive? Start by forgetting what some action might mean to you, and instead look carefully at how the dog responds. He’s the one who defines what is aversive and how strong an aversive was used. With a very scared dog a hand clap could be terrifying, but for typical dogs it’s only a mild startle that’s quickly forgotten. I’ve had dogs where I initially had to whisper commands and others who needed shouts. For that last case, history is also a qualifier for aversives. If a dog becomes habituated to people yelling at him or pulling back on a leash, he may simply ignore those actions.

The Tale of the Tail

So many times I’ve heard people describe what a dog is saying by just looking at the tail. Then came the books and articles adding more and more body parts, most of them insisting that this-means-this and that-means-that. Along the way came a very few books like Tail Talk (Sophie Collins) that explained it wasn’t so very cut-and-dry, and tried to put this in a more practical perspective. But, people always tend to like simple rules best, even when they don’t really work.

But how are dog trainers with this? I recall one who was watching a shelter play group I was running, and explaining to some people what the dog’s body language meant. For all that, she stayed outside the play area. It was the handlers working inside who knew enough about body language to actually predict, not what the book would say, but what the dog was going to do next.

For, in the end, the accuracy of your behavior predictions is the only true test of how well you understand the dog’s body language. And several aspects of this are often omitted in those articles and pretty pictures describing dog body language.

One of the missing components is intensity. Some dogs will only do a tail tuck when really scared. But a few others will do it when they are only slightly startled. One dog when annoyed by another may just freeze and look away, while another may bark and air-snap at the offending dog first, even though no more annoyed than the first dog. While I’ve used a few extremes to make the point here, they do vary quite a bit. You can always make a first guess, but then you can only accurately calibrate a particular dog by first observing his behaviors in that situation.

Another area is understanding predation practice behaviors, which originated in another scenario. Stalking, chasing, and pouncing are behaviors that would be used to capture prey and obtain food. Yet these same behaviors are in common play forms used by dogs, without any intent to cause harm, but in a manner that allows the behaviors to be practiced. While some use only a loose approximation, other dogs may assume body language that is identical to what they would use in pursuing prey. And the only difference you may see is in those dogs remaining very responsive to the other dog’s signals, and avoiding any harm.

So if more than one dog is involved, be sure to look at the other dog. Both in his reactions, and if his signals get a response from the first dog. If only you and a dog, you may need to apply a controlled stimulus to clarify the dog’s response. I once demonstrated this with two Rottie’s and several Dog Trainers. Both dogs showed identical body language (they couldn’t tell any difference) of heads up and ears back and flat. This actually means indecisive anxiety, which could be due to defensive aggression, or not. I slowly approached each dog, while holding a ball in front of me. One dog curled his lip and growled, but the other just popped up and got ready to run after the ball. She was excited (anxious) when she saw the ball, but indecisive on how to get me to throw it.

Finally, there are the simple assumptions. A nervous dog sees a friend wildly play-fighting with another dog and attacks them. Many dog owners quickly say she’s protecting him, instead of realizing it simply makes her very nervous and she wants them to stop. She has not learned that she should simply move further away to settle her nerves. Assuming she is protecting another dog or person is not just common with dog owners, but also many Dog Trainers.

And, think about that one. Typically the aggressive dog may have seen the two other dogs play many times before, has seen from their body language that they both want to play, and that they are both enjoying the play. If neither of the playmates gives any indication of distress, exactly what would the aggressive dog be protecting?

Many people really want to follow the tail

For several years I had followed Observation Skills for Training Dogs, a now archived group on Facebook. When the group first started, it seemed there were a number of nice discussions on observation and interpretation of a dog’s body language, but this changed over time. The group leader and others supplied a number of guides to dog body language, with many of them giving simple and hard rules. New people came in, following their natural tendency to both speculate on information not available, or on the dog’s state of mind. While it can be fascinating to guess at what a dog is thinking, looking at his state of mind is quite different from predicting his behavior. Perhaps the difference between a dog being happy or sad, and if the dog is going to play or bite. And people not only took the dog guides to extremes, but they often ignored other components of body language which showed a different picture, such as looking at:

Ears back, furrowed brow, head turns away, whale eye, tongue flick, panting, licking.

While ignoring:

Stays in place, moves closer and solicits attention, relaxed body and legs,

Bringing to mind a phrase about this from a well-known behaviorist:

Dr. Ian Dunbar

And, it seems that once those people had accepted those very simple rules, they would defend them to the end and not consider any changes.

While some of their own guides noted that one should always look at the dog’s total body language, they continued to focus only on what seemed most significant to them. And trying to convince them to look at both the other dog and the entire behavioral sequence, all just fell on deaf ears. I believe there were hundreds of people in this group, with none receptive to any real discussion.

Even in dog parks, where people get a good chance to observe a variety of behaviors from a diverse group of dogs, many of these items persist, which just implies that this is a natural characteristic of most people.

Capturing, Clickers, and Command Cueing

For this section, you need some familiarity with clicker training and behavior capture. The great Web is full of references ranging from Psychology Today to Dog Training Excellence, and of course the Karen Pryor Academy.

When capturing new behavior during clicker training, they say to introduce the command cueing when the dog is performing the behavior reliably. But there are often some problems with that approach, so let’s look at both ends of it.

If you start using the cue before the dog can associate it with the behavior, there can be no learning that would relate them. If you wait until he does the behavior reliably, you may have wasted quite a bit of time. So, as soon as the dog has done the behavior just a few times, start using the cue word, but only if and when the dog just begins to commit to the behavior, or basically the same time you use the clicker. As reliability slowly increases, start moving the cue word back in time. Yes, there may be a few times when you use the cue but don’t see the behavior, but that’s going to happen in any case, just not too often.

Now let’s look at what commit means here. If teaching a dog to sit, it makes little difference if you wait to click until his butt hits the ground, or if you click while he’s on the way down. But when teaching retrieval, the time to click is when the dog has just started moving towards you. Not when he turns around or lifts a paw, but when he actually starts moving. And this agrees with most clicker training literature.

And then there’s the question of if the behavior should be prompted for capturing, or you just wait until it happens by accident. In most cases, some general scenario is set up to prompt or increase the likelihood of the behavior being performed. If I stand quietly in front of a dog with my hand high and over his head so he has to look up and just wait, many dogs will then do a sit, and the behavior can then be captured. So, in a large sense, you are still prompting the behavior with a cue, even though they may not call it that.

There has been some research to indicate that purely captured behavior becomes more persistent somewhat faster than prompted behavior, but the data is currently rather weak on that. I’ve heard a number of Dog Trainers explain that it happens because the behavior is something that the dog themselves decided to perform, but there’s nothing anywhere to support that.

On the other hand, we do very clearly know that learning persistent behavior is enhanced by repetition. That if I try to purely capture an incidental behavior it may be many minutes between each repetition. But if I am able to prompt the behavior and obtain a hundred times more repetitions, that will have a clear enhancing effect.

Fanatics are Made, Not Born

I have both heard and seen, that often people who have converted to any religion tend to defend that religion stronger than those who were raised in it. Perhaps a similar mechanism applies to dog trainers who first started with forceful and dominance approaches, before later seeing the light of Positive Reinforcement (+R).

Over and again, I see their articles, decrying dominance approaches, and claiming that it has recently been a huge topic and a hot debate. Yes, there are those people who know little and only watched the popular shows on Dog Whispering and such. Yes, some of that will linger for many more years, but I think most of the actual debate was settled years ago.

Some of these people then seem to become +R Fanatics, preaching only a small portion of reinforcement-based training, and claiming a total solution here. Fortunately, it’s generally a kindly solution and one that often works. But when it doesn’t or takes a very long time, they claim that as simply the way things are.

While some have claimed to have read countless books on the topic, that really isn’t necessary. About two dozen of the correct books would have taken them further. However, let’s look at an article titled Why Not Dominance.

In that article I agree with much of what she says, especially when she brings up that many people lack patience. Well, of course they do. When somebody is very frustrated, it does little good to keep telling them to use +R and never punish. But what they fail to realize is that teaching others how to train dogs must also include some human behavior in the mix, and how people might react there.

And take the case of a dog who wants to perform a behavior you do not want him to, and if he enjoys that behavior more than most any food or other reward you could give him for not doing it. There are scientific, established, and minimally aversive techniques that will often work, while +R alone will not, but those fanatics don’t look any further.

Extreme Clicker’ing and Tunnel Vision

The following was posted by a large shelter’s behavior specialist (Albuquerque), about their use of clicker training:

Clicker training is a method for training animals that uses positive reinforcement such as a food treat, along with a clicker or small mechanical noisemaker to mark the behavior being reinforced. When training a new behavior, the clicker helps the animal to quickly identify the precise behavior that results in the treat. The technique is popular with dog trainers, but can be used for all kinds of domestic and wild animals.

Clicker training is one of the only styles of dog training which is actually based on scientific research. While other training styles are based on theories which are unsupported or even contradicted by scientific research, clicker training is based upon Classical and Operant Conditioning, which are some of the most thoroughly proven psychological theories.

However, Clicker training is not one of the only styles of dog training that is actually based on scientific research. A statement such as that is downright silly, as it is simply one form of positive reinforcement with token replacement, and not the only one of that type either. Perhaps its greatest advantage is that it is relatively easy for many people to learn. Yes, there are some poor and unscientific training methods, but there are many other variations that are firmly based on science.

Many of the other things taught in a typical clicker training course are important but have no direct connection to using a clicker and apply equally to other approaches. But like all approaches, clicker training does have its limitations and is not efficient for certain issues or situations. In other words, nothing in this world is perfect, and those who ignore that simply fail to understand the nature of what they are doing. It’s just fine to emphasize and promote the advantages of clicker training, but their extreme is poorly advised and not productive.

Since we do mostly understand that nothing is perfect, I find it useful to ask Dog Trainers, no matter what approach they advocate, if they understand the limits of their approach. A question that does seem to make many of them very defensive and argumentative. But, only by knowing its limits might they actually understand what they’re really talking about.

In some of this shelter’s posts, they also reference articles from the ASPCA and elsewhere, none of which support some of their claims. As for her claim of clicker training being based upon both classical and operant conditioning, a check at the Karen Pryor Clicker Training web site only relates it to positive reinforcement, which is only one particular aspect of operant conditioning.

As for tunnel vision, it’s an often seen characteristic of many people that, if they have invested much time and effort in studying only one approach or technique, they will see that as greater than it is, always promoting and defending it. And they are rarely learning its limits, especially if they have only a limited understanding of the principles on which it is based. And this example was from a certified trainer.

The Balanced Pack

At a few dog training websites I see comments such as:

When it comes to helping dogs find self-confidence and behavioral balance nobody, I mean nobody, can do it better than a Pack of balanced dogs!

Regardless of whether it’s a lack of early effective socialization, fears or phobia’s, Separation Anxiety, dog or human aggression, etc. – nobody can rehabilitate a dog in need like a Pack of balanced dogs.

While there are clear and obvious advantages to using other dogs, let’s take a little closer look at this. We might all agree that playing tennis helps you to develop your tennis skills, but few would argue that it also improves your soccer game. And that applies here, in several different aspects.

First, as we lack tails and other accouterments (and species distinctive behaviors), we can’t really teach a dog the social skills to use with other dogs. There, a group of well-mannered dogs is very useful. In this, my use of manners applies to typical conspecific (within the same species) social skills that dogs use to negotiate play and access to resources and to prevent fights. As for their label of balanced dogs, I’m not sure just what that means, nor do they ever explain.

Next, what they may learn in that group will be limited by the other dogs’ behaviors. If they are all very sedate, he doesn’t learn vigorous play. If they are all very playful, he doesn’t learn proper manners to use with sedate dogs. There are also some dogs who correct others far more often, scared dogs who need to be gently handled, and very tolerant dogs who simply ignore a great deal of bad behavior. Perhaps their balanced actually means a variety such as this, but that I don’t know.

Next, there is a skill difference between slowly meeting dogs over a period of days, and only initial meetings. Some dogs who come into a new house adjust well in a few hours or days, but when initially meeting a new dog become very anxious. Just as with people who slowly become comfortable with their coworkers, but are often very nervous when starting a new job. But if your job changed to one where you were constantly meeting new people, you would pick up on that skill. And for that reason, I use a local dog park, no matter how many other dogs I may have here at the time. Many adopters already have a dog, and it’s important that the initial meeting goes well. This gives them the opportunity to learn how to meet a wide variety of personalities.

Finally, those websites list things that have nothing to do with a dog’s social skills. If they have separation anxiety, human aggression, or fear of cars, then no pack of balanced dogs can teach them to overcome those issues. Yes, it may make them calmer and with more self-confidence, but that primarily relates to social behavior with other dogs. No matter how good you become at tennis, you may continue to stink at soccer.

A few might argue that they will pick up on the other dog’s behaviors in those situations. There I’ve seen shelters try to put rowdy dogs next to well-behaved ones, but to no avail. No matter how many soccer games the tennis player watches, his soccer may only slightly improve from a very few things he picks up on. And that’s with people, who are capable of far greater abstraction and generalization than dogs.

The Absolute Best Training Method

So what’s the best way to train a dog, we ask? Nobody can answer that, as it depends on several things. From the dog’s personality and current issues, to the environment in which you’ll be teaching, and finally limited by those approaches that you are both willing and able to perform. So any reasonable approach meeting all that might well be considered.

Another criteria for choosing could be an ethical one, such as Stephen Lindsay’s LIMA Principal, that you should always try to choose the method being Least Intrusive and Minimally Aversive.

In general, we know that not all dogs are the same. We know that not all people are the same, with differing knowledge, skills and interests. We know that resources may differ, in available time and facilities. So how could there be any single best training method?

When working directly with a dog in rehabilitation here, being retired I have the time to spend with them. I have good facilities and several dogs who are trained and experienced in working with issues. I first spend several days diagnosing the issues, determining the dog’s general personality characteristics and learning rate, and their current learned behaviors and anxieties. From this I may very briefly try several different approaches, noting their response to each, before deciding what approach is both effective and efficient. While they always include some of the basics noted earlier, the rest will vary considerably.

When I support a foster with problems, as the dog isn’t here there’s much less information to work with. As with many of the better Dog Trainers, we have to make some initial guesses based on what we see and prior experience. Then check back in a few days or a week, and make adjustments, usually after actually seeing how the person is performing the exercises with the dog. Even if you give people a set of steps with pictures, and even if you’ve demonstrated and had them demonstrate for you, a week later some things will have changed.

And there will be limits. A dog who is naturally nervous and scared may always be so, just with the dog and person both learning how to better deal with it.

References

Today, the World Wide Web contains articles and blogs which can support virtually any conceivable view or opinion. For general articles on dog behavior, I’ve found these few to be generally accurate and relevant. There are many general discussion blogs, but far too many of their comments are incorrect, incomplete or highly biased. There are a number of veterinary behaviorists and certified behaviorists who may seem like ultimate experts, but some make statements conflicting with current science (or other behaviorists) or give absolute rules that often fail.

- Dr. Karen Overall

- Dr. Ian Dunbar

- Dr. Nicolas Dodman

- Stephen Lindsay

- Dr. Patricia McConnell

- Jean Donaldson

Jennifer Cattlet is an ethologist and behaviorist with decades of experience with dogs. She often takes and summarizes various studies on aspects of dog behavior and training.

Linda Case is a science writer and author who specializes in canine health, nutrition, behavior and training. From that you have a variety of topics, from what you feed your dog, to issues with behavioral assessments at dog shelters.